- Evidence Snacks

- Posts

- Habit inertia

Habit inertia

The double-edged sword of teaching

Hey 👋

Welcome to June—the dawn of summer, or winter, depending on your latitude. Today, we extend the theme of teacher expertise with the notion of habit inertia…

Big idea 🍉

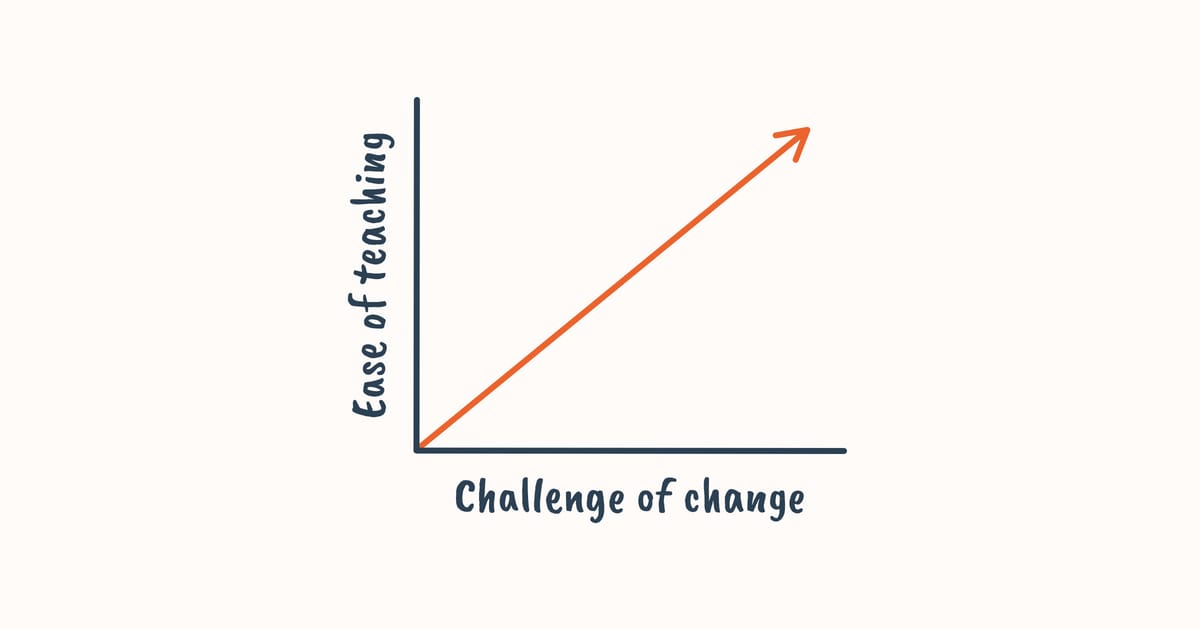

Habits enable effective teaching. But they also inhibit professional development, due to their ‘inertia'.

↓

First up, a habit is:

A chain of actions

That gets executed on a prompt (aka 'cue')

All of which happens with minimal mental effort and conscious control (they are ‘automated’ thoughts & behaviours)

For example, when your alarm goes off in the morning, you get up, shower, dress, and have breakfast—all without really thinking about it. Like an autopilot.

Habits are crucial in teaching. In most lessons, there are vast swathes of data to process and decisions to be made—it’s only when we automate much of this that we can begin to cope with, and eventually master, the extreme cognitive demands of the busy classroom.

Furthermore, this is what typically trips us up when we first begin teaching. New teachers have not yet automated many aspects of their practice, and so have to consciously think through every event and decision they encounter. This rapidly becomes mentally overwhelming.

Teaching only begins to get easier as our perception, decision, and action begins to automate. With sufficient experience, so much of teaching becomes habit that we even have mental capacity to spare 🏄

When this happens, teachers find themselves able to acutely monitor the whole class even in the midst of an exposition or when working closely with an individual. And do all this while responding flexibly to individual needs as they arise.

“We do not rise to the level of our goals. We fall to the level of our systems.”

Habits are the basis of effective teaching. However, they also come with a cost.

The unconscious, automatic nature of habits makes them notoriously resistant to change. The more established the habit, the more entrenched it becomes. This is 'habit inertia' and it creates a challenge for teacher development.

When experienced teachers try to change, they must devote extra mental effort to both execute the new practice and suppress any old habits they are trying to replace. This can make teaching feel clumsy, and remove that precious bandwidth reserved for monitoring and responding.

Changes in practice also disturb the delicate expectations and routines of the class. Which lead to increased pressure and stress for the teacher. And guess what: under pressure, we are more likely to revert to previous habits.

The more experienced we become, the more these risks prevail. This is one of the main reasons why teacher growth is prone to plateau, and why it’s just as important (if not more so) to ensure experienced teachers have access to effective development opportunities, not just those new to the profession.

Challenge → How ‘habituated’ is your teaching? How do you manage the delicate balance between maintaining fluency and integrating improvement?

Summary

• It’s only when we automate much of our teaching that we can manage the vast complexity of the classroom.

• However, the more habituated our approaches become, the harder they are to change.

• Experienced teachers stand to benefit from effective professional development as much as newer teachers.

Little links 🥕

On topic → Check out this cracking paper on habit formation and teacher effectiveness by Hobbiss et al., and here’s a deeper dive into the factors which influence habit formation.

On trend → A new study on the effects of a self-study intervention (in HE), a review arguing the case for adding inquiry approaches to direct instruction, and a (fairly bleak) evaluation of the Reading Recovery programme.

Enjoy yer crackers, Evidence Snackers.

Peps 👊

PS. If you lead teacher development in your organisation, I’ve got a quick question for you: